| Monument | Date (A.D.) | Ruler |

| Preah Ko, Roluos | 879 | Indravarman I |

| Bakong, Roluos | 881 | Indravarman I |

| Lolei, Roluos | 893 | Yashovarman I |

| Prasat Kravan | 921 | Harshavarman I |

| East Mebon | 953 | Rajendravarman |

| Pre Rup | 961 | Rajendravarman |

| Ta Keo | late 10th c. | Jayavarman V |

| Angkor Wat | first half of 12th c. | Suryavarman II |

| Ta Prohm | 1186 | Jayavarman VII |

| Preah Khan | 1191 | Jayavarman VII |

| Ta Som | late 12th c. | Jayavarman VII |

| Hospital Chapel | late 12th c. | Jayavarman VII |

| Angkor Thom | early 11th - late 12th c. | Suryavarman I - Jayavarman VII |

| Spean Thma | 16th c. | Unknown |

See also: Angkor Kings and Monuments

The Angkor Site

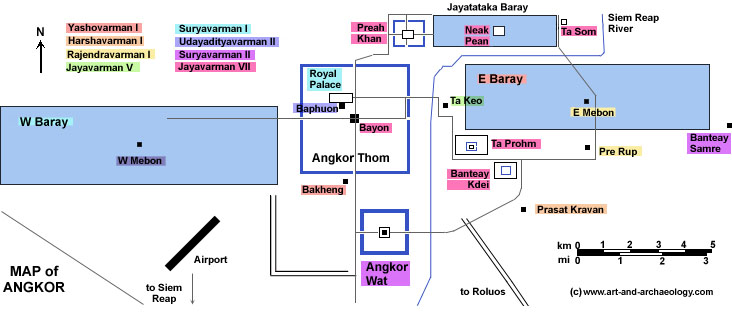

The first thing to notice about Angkor is the sheer scale of things. The map above covers about 18 miles x 8 miles in area; Siem Reap's airport could fit easily into the West Baray, with most of the Baray left over. The prosperity of the Khmer state was determined by an unfailing abundance of three resources: fish, rice, and water. Angkor, the capital of the Khmer empire from 802 to 1431, is well-placed on the northern margin of the Great Lake, to take advantage of the inexhaustible supply of fish which the lake produces. Equally important was plentiful water for farming rice. This water was supplied by rains and rivers, stored in artificial reservoirs, and distributed to the rice fields by irrigation canals.

Ultimately Angkor, like all empires, fell. There are currently (as of 2018) two theories about this, both of which are supported by good evidence: (1) Angkor grew beyond its means, a dense urban political and religious core surrounded by a vast lower-density periphery, or "sprawl," that was eventually overrun by invaders from the periphery; and (2) Severe climate change led to alternating draught and floods, that both wrecked the harvests and destroyed the engineering infrastructure that sustained them.

Political History

The Khmer empire began with Jayavarman II,

who freed his kingdom from Indonesian rule and

absorbed other local kingdoms into his own. Jayavarman established his capital first at Hariharalaya (near the modern village of Roluos), then moved to Phnom Kulen where he proclaimed himself emperor in 802,

and finally returned to Hariharalaya towards the end of his reign.

The capital was moved to Angkor by Yashovarman I, who built

the capital of Yashodharapura ("The Glorious City") at Angkor

centered around Phnom

Bakheng. Following a brief interlude at Koh Ker under Jayavarman IV,

the capital was returned to Angkor by Rajendravarman in 944. Following a succession struggle at the beginning of the 11th century,

Suryavarman I gained control of the kingdom, built the Royal Palace

and West Baray, and expanded the empire's frontiers into

Southern Laos and as far as Lopburi in Thailand. His successor,

Udayadityavarman II, faced a succession of revolts that

culminated in a defeat of his successor, Harshavarman III, by the

Champa kingdom of Southern Vietnam.

The Cham threat was overcome by Suryavarman II, who in 1144 defeated the Chams and sacked their capital. Suryavarman II reestablished

diplomatic relations with China; extended the Khmer frontiers

into Thailand, Burma, and the northern Malay Peninsula; and built

the great temple of Angkor Wat. However, his expensive building

programs and military-political expansionism, particularly an

unsuccessful invasion of North Vietnam, seriously overextended the

empire, which was beset with difficulties after Suryavarman's death

in 1150. In 1177, the Chams invaded and sacked Angkor.

The Khmer empire was reestablished by Jayavarman VII. A devout Mahavana Buddhist, Jayavarman spent the years before his accession as a

voluntary exile in the Cham capital. Upon becoming king, he

defeated the Chams (1181) in a great naval battle on the Tonle Sap

lake, pushed the empire outward to its greatest extent, and

undertook a massive building program that included Angkor Thom, Ta Prohm, and Preah Khan. After Jayavarman's death, an iconoclast

reaction set in, and many Buddhist images were destroyed. Nevertheless, by the 14th century all of Cambodia had adopted

Theravada Buddhism. The empire gradually declined under

Jayavarman's successors, due especially to military pressure

from Ayutthaya; Angkor was abandoned after being conquered and sacked by the Thais in 1431, although it was briefly

reoccupied in the 16th century.

The Barays

The first great barays in the Angkor region were Indratataka

at Hariharalaya, built by Indravarman I in the late 9th century, and

the East Baray at Angkor, also begun by Indravarman but completed

by his son and successor, Yashovarman I.

The East Baray is a monumental artificial lake

measuring 1.8km by 7.5km, which is 1.1 miles wide and 4.7 miles

long. As with all the great barays, it was built by excavating

and piling up an enormous earthen retaining wall, about 4m-5m (14') tall,

around the perimeter, so that the water was held above ground behind

what is, essentially, a giant dyke.

The East Baray was fed by the Siem Reap river, and would have

held 37.2 million cubic meters of water at a depth of 3m (10').

(A figure of 55 million cubic meters of water is also quoted;

the larger figure assumes an average water depth of 4.5m).

The amazing scale of such a construction, and the

amount of labor (about 10,000 man-years) necessary to dig and pile

up the reservoir walls, can hardly be put into adequate words. Most likely the water was used for irrigation (this has been questioned, but recent surveying and satellite imagery seem to confirm it).

Waterworks on this scale must also have had stunning religious and political implications.

The major problem with the baray system was siltation - the gradual

influx of sand, carried by the river, into the reservoir. The

East Baray was completed around 890. During the next century, as

it gradually became filled up with sand, it was periodically

renovated by raising its banks, and new, smaller, barays were

constructed to supplement the water supply (Srah Srang, east of

Banteay Kidei, mid-10th

century). The enormous West Baray was completed in the mid-11th century, followed later by diversion

of the Siem Reap river around the East Baray and into

excavated canals.

The last great baray at

Angkor was the Jayatataka, built

by Jayavarman VII (1181-1218). By the mid-13th century, the baray

system had exhausted itself, as the process of siltation outpaced the

ability of the Khmer to raise the height of the reservoir walls.

Subsequently, stone

bridges were used as dams. These could be blocked up to create a

reservoir behind the dam, or unblocked to feed water through a

system of canals. For example, a dam was built between

the south bank of the Jayatataka and the north bank of the East

Baray, to back up the flow of the Siem Reap between the two

barays. Unfortunately, these dams had a

design problem. Their earthen dykes could become weakened due to erosion,

and subsequently break. This happened at least twice: in the

13th century at the Jayatataka, causing a major flood to the

east part of Angkor, and in the 16th century at Spean Thma

(damming the river just west of Ta Keo.)

The later flood was so extensive that it rechanneled the Siem Reap river into its present course.

Angkor Thom and Angkor Wat

Recent studies (Remapping the Khmer Empire, Archaeology Magazine, J/F/2014) have verified that the full urban area of Angkor Thom extended well beyond its enclosing moat to include the earlier temple center of Angkor Wat. The map above illustrates the full extent of Angkor Thom, as it is presently understood, via a schematic diagram of its SW corner: the set of right-angle lines that extend from Angkor Wat to the east end of the W Baray.

|