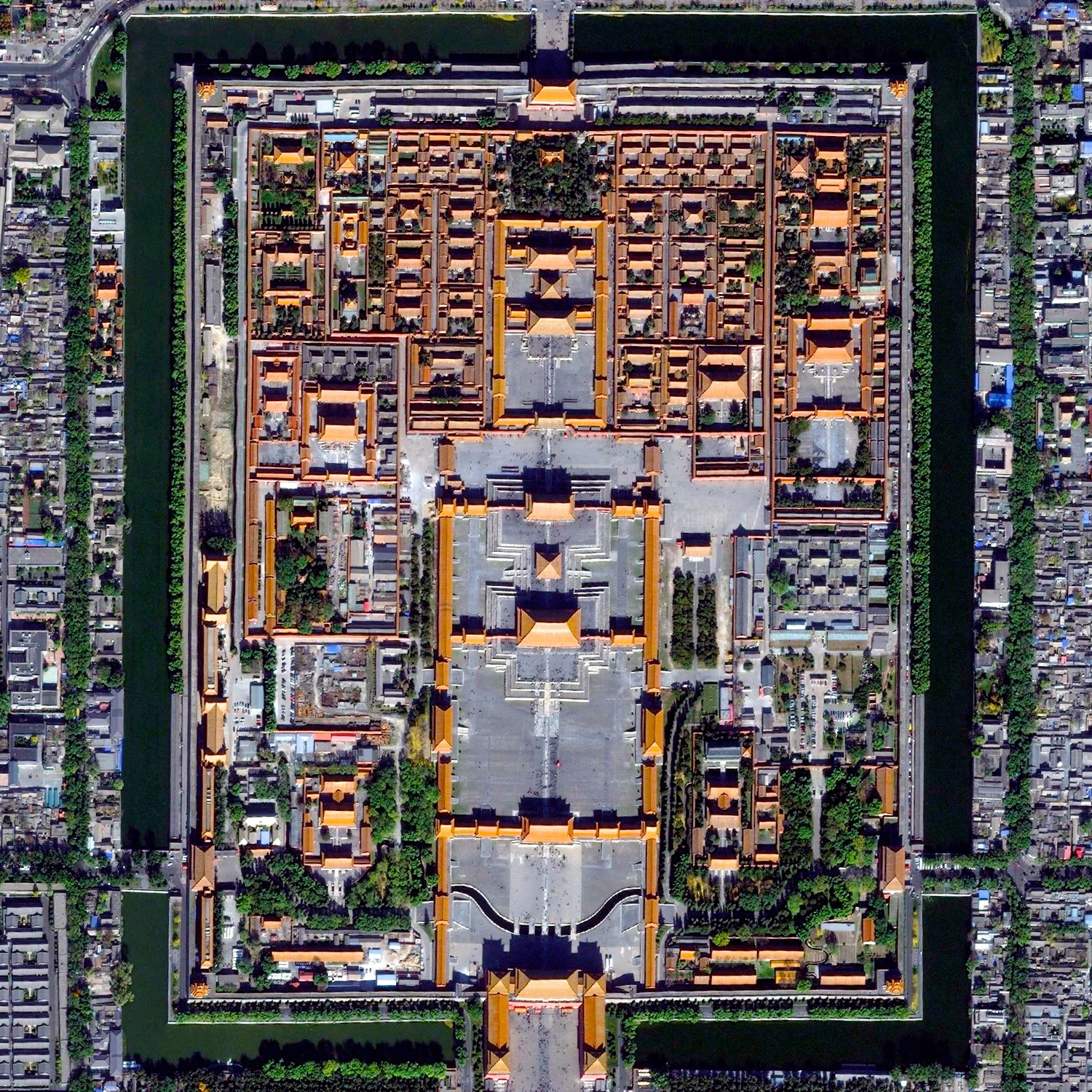

Photo: Palace Museum

Photo (modified): Wiley Publishing, Inc.

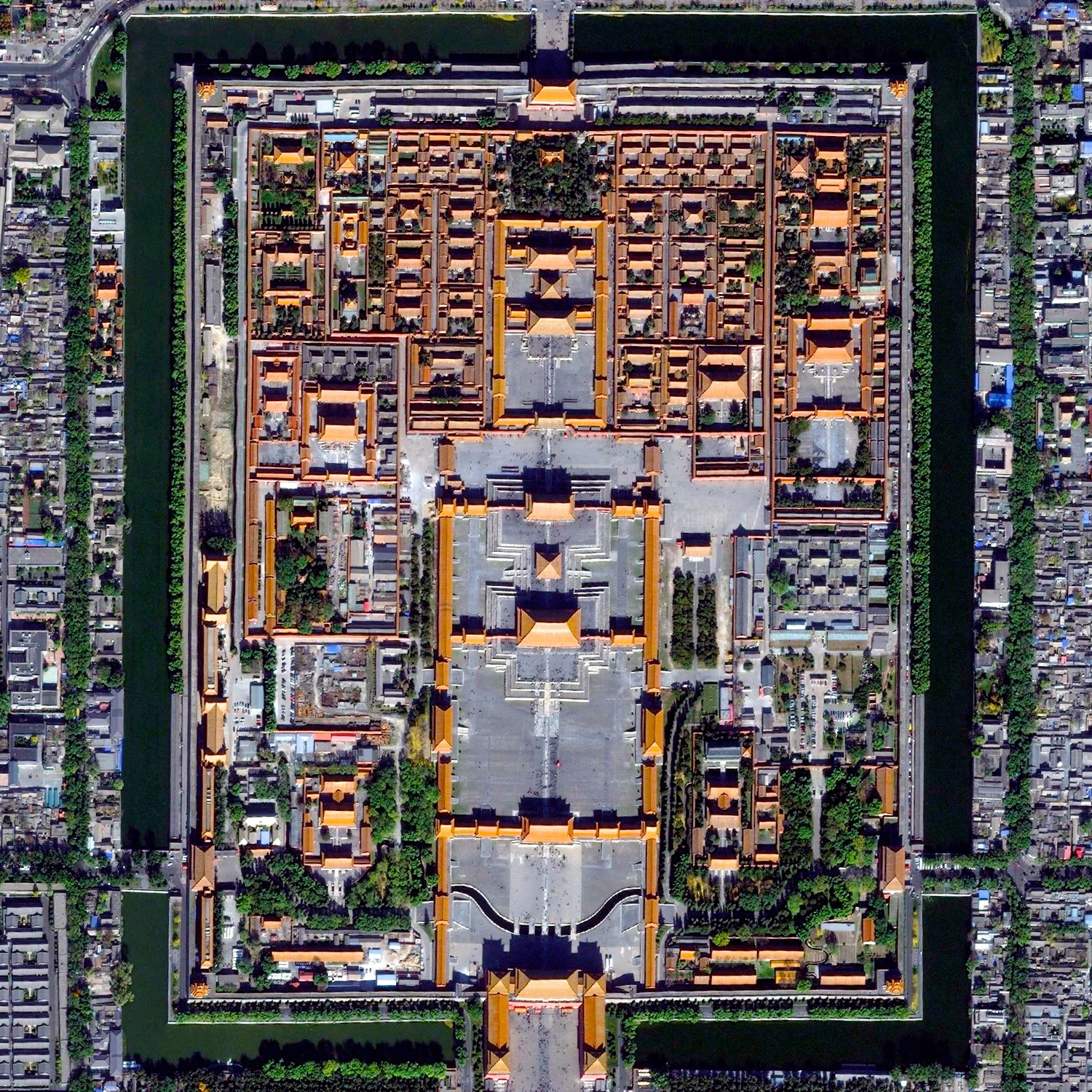

Photo: Palace Museum |

Photo (modified): Wiley Publishing, Inc. |

Beijing

Ming-Qing Dynasties, 15th-19th century

Construction on the Forbidden City, China's seat of government and home of the emperors for 500 years, began with Yongle, the second Ming emperor, in 1407. The Forbidden City was sacked at the end of the Ming dynasty, but was repaired after the Qing came to power. Its present layout mostly follows the plan of Qianlong's 18th century refurbishment. In 1919 the last emperor, Pu Yi, abdicated but continued to live in the palace. Pu Yi was finally expelled in 1924, after which the entire complex was turned into a museum. All of the buildings are made of wood; the Forbidden City, with its 9,000 or so rooms, is the largest collection of wooden buildings in the world.

Six major palaces line up along the city's north-south axis. Starting at the main entrance (south end of the complex, the Meridian Gate) and moving north, the visitor first crosses a set of five marble bridges, then passes through the Gate of Supreme Harmony and across a very large ceremonial courtyard to reach the outer palace compound (Halls of Supreme Harmony, Middle Harmony, and Preserving Harmony) where the emperor conducted public business. Behind this is the inner palace compound (Palace of Heavenly Purity, Hall of Union, and Palace of Earthly Tranquility) that was the private Imperial quarter. A garden backed the inner palace to the north. A maze of courtyards, east and west of the central axis, housed offices and quarters for concubines, servants, and members of the Imperial Family. In the following pages, the description of individual buildings is based on Shi Yongnan and Wang Tianxing (ed.), The Former Imperial Palace In Beijing.

The daily life and movements of the emperor were governed by ceremony: north to south, from his private to public spaces, and back again, always carried everywhere in his sedan chair. His officials, only the most privileged of whom were permitted access to the Forbidden City at all, moved in the opposite direction, from the southern Meridian Gate up north along the axis to the public buildings of the Outer Court.

The tour on the following pages begins just outside the walls, proceeds northwards up the major axis, then to one of the western palaces and out to the Imperial Garden. To avoid interrupting the architectural flow, I exhibit photos of roof trim, incense burners, and other palace decoration in a separate chapter.

|

|