Baodingshan Rock Carvings, Dazu

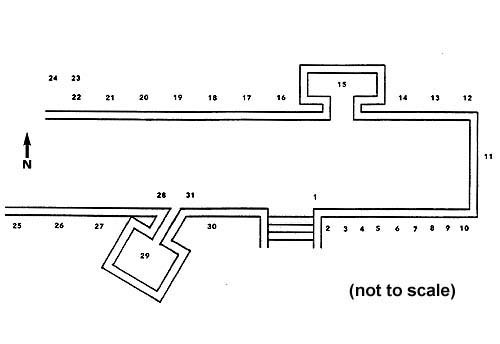

The Buddhist grottoes at Baodingshan, 20km northeast of Dazu, were carved during the Southern Song Dynasty, under the direction of monk Zhao Zhifeng, betweeen 1179 and 1249 AD. The Daoist images #23-#25,

however, date to the Qing Dynasty and later. The site is bent

into the shape of a hairpin, about 500m long from west to east,

giving about one kilometer total length of sculptures; the carved

areas are between 3 and 15 meters tall.

Zhao's purpose at Baodingshan was to re-insert Buddhism, which at the time was perceived as a foreign religion, back into the native Chinese tradition. For example, Confucian scholars had criticized Buddhism as lacking in filial piety, a charge which Zhao refuted in several of the reliefs at this site.

Religiously speaking, these reliefs and sculptures reflect an eclectic school of Esoteric Buddhism (#4, #15) that emphasized the cult of Liu Benzun (855 - 907), a saintly layman of Sichuan province who became revered for his austerities (#22) and spiritual perfection (#27). Huayun (#5, #15), Pure Land (#19), and Chan

(#29, #30) are represented, admixed with Confucianism

(#16, #18). Other scenes include Shakyamuni's

birth (#12, #13) and death (#11); the Wheel Of Reincarnation (#3);

Hell Punishments (#21); and popular deities (#2, #8, #14, #17).

The purpose of these reliefs is variously devotional, didactic, and homiletic. They are interspersed with numerous quotations from the sutras, like illustrated sermons in stone; their theme is the pursuit of transcendence, as expressed by Zhao's signature text:

|

|

Even if one spins a burning hot iron wheel on top of my head,

No matter how excruciating the pain is,

I will not relapse from the mind of enlightenment.

|

The reliefs are artistic, lively, and down-to-earth.

They must have appealed to the common people, as well as to elite persons of the time. Many scenes involve ordinary people and situations, and were used as parables or teaching devices. They illustrate Zhao's religious doctrine in a concrete and memorable way, originally for the monks who trained at the site, and no less so for visitors today.

The sequence of reliefs amounts, in effect, to a handbook on salvation. Zhao uses many means to this end: reflections on Shakyamuni's

life (the Parinirvana and Birth reliefs) and the doctrine of Karma (the Wheel of Reincarnation); encouraging good acts (reliefs of Parental

and Filial Kindness) and discouraging evil acts (Hell reliefs); and promoting various kinds of worship (Huayun, Pure Land, and Esoteric reliefs) and contemplation (Oxherding Parable). In this way, Zhao promotes the Mahayana ideal that everyone can be saved, through various means as necessary.

The following pages illustrate most of the Baodingshan site, proceeding counterclockwise from the entrance. Only a few very damaged reliefs (#7, #9, #10, #26) are not shown. Even more information and photographs

can be found in Angela Falco Howard's

Summit Of Treasures (Weatherhill, 2001), the standard English-language reference for Baodingshan and the other Dazu sites. I am indebted to Howard's book for greatly enhancing my own appreciation of Baodingshan's treasures.

In art-historical terms, there are two very different styles of carving on the human figures. Foreigners in general, which in the context of Baodingshan means people from India or Central Asia, are rudely carved with wide mouths, square jaws, and exaggerated features; typical foreign types include guardians, Brahmins, demons, diplomats, merchants, and entertainers. Chinese people, on the other hand, are delicately carved with polite mouths, narrow jaws, and subtle Han features. Buddha is the exception; looking like no other except himself, his physiognomy had been established in Chinese art by at least the Tang dynasty, five hundred years before Baodingshan was carved.